Java - Multi Threading

Nearly every operating system supports the concept of processes – independently running programs that are isolated from each other to some degree.

For e.g. when you are using a computer you can browse internet while listening to the music, or using word processed or accessing other folders at the same time.

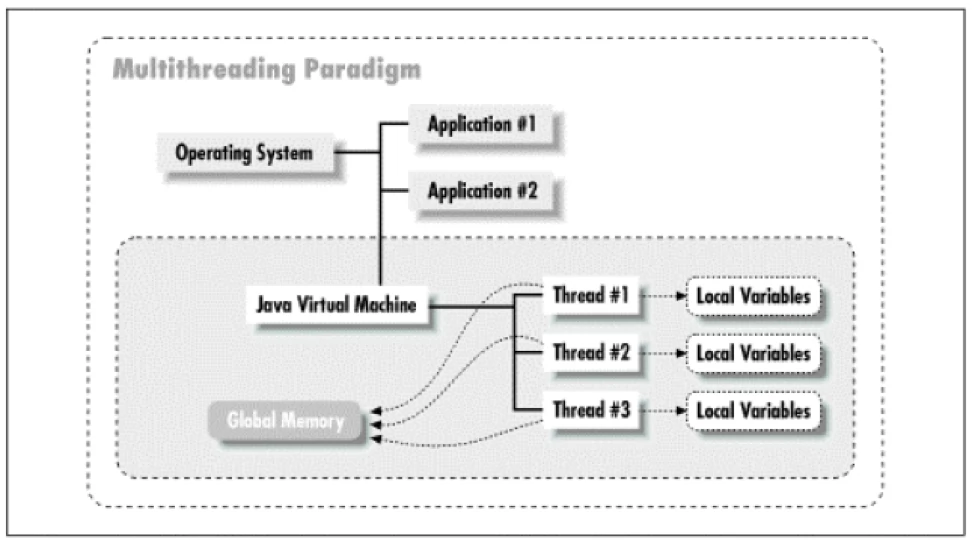

Threads are sometimes referred to as lightweight processes. Like processes, threads are independent, concurrent paths of execution through a program, and each thread has its own stack, its own program counter, and its own local variables. However, threads within a process are less insulated from each other than separate processes are. They share memory, file handles, and other per-process state.

A process can support multiple threads, which appear to execute simultaneously and asynchronously to each other. Multiple threads within a process share the same memory address space, which means they have access to the same variables and objects, and they allocate objects from the same heap. While this makes it easy for threads to share information with each other, you must take care to ensure that they do not interfere with other threads in the same process.

Because multiple threads coexist in the same memory space and share the same variables, you must take care to ensure that your threads don’t interfere with each other.

Why use threads?

Some of the reasons for using threads are that they can help to:

- Increase the responsiveness of GUI applications

- Take advantage of multiprocessor systems

- Simplify program logic when there are multiple independent entities

- Perform blocking I/O without blocking the entire program

There are several ways to create a thread in a Java program. Every Java program contains at least one thread: the main thread. Additional threads are created instantiating classes that extend the Thread class or by implementing the Runnable interface.

Thread class and Runnable Interface

A new thread is born when we create an instance of the java.lang.Thread class or java.lang.Runnable interface. The Thread object represents a real thread in the Java interpreter and serves as a handle for controlling and synchronizing its execution. With it, we can start the thread, stop the thread, or suspend it temporarily.

You’ll find methods in the Thread class for managing threads including creating, starting, and pausing them. For e.g.

- start()

- yield()

- sleep()

- run()

The action happens in the run() method. Think of the code you want to execute in a separate thread as the job to do.

public void run() {

// your job code goes here

}

You always write the code that needs to be run in a separate thread in a run() method. The run() method will call other methods, of course, but the thread of execution—the new call stack—always begins by invoking run().

Defining a Thread

To define a thread, you need a place to put your run() method, and as we just discussed, you can do that by extending the Thread class or by implementing the Runnable interface.

Extending java.lang.Thread

The simplest way to define code to run in a separate thread is to

- Extend the java.lang.Thread class.

- Override the run() method.

class MyThread extends Thread {

public void run() {

System.out.println("Important job running in MyThread");

}

}

The limitation with this approach (besides being a poor design choice in most cases) is that if you extend Thread, you can’t extend anything else. And it’s not as if you really need that inherited Thread class behavior, because in order to use a thread you’ll need to instantiate one anyway.

Implementing java.lang.Runnable

Implementing the Runnable interface gives you a way to extend from any class you like, but still define behavior that will be run by a separate thread.

class MyRunnable implements Runnable {

public void run() {

System.out.println("Important job running in MyRunnable");

}

}

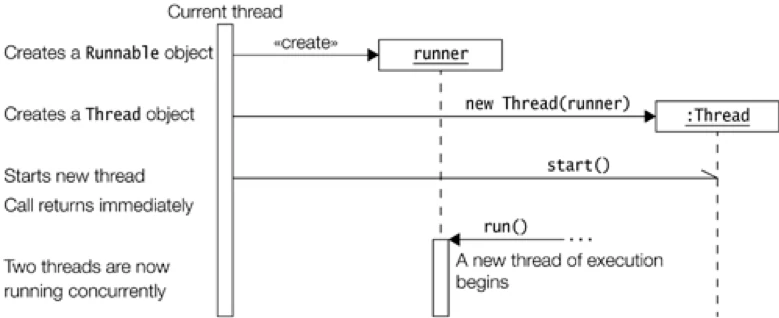

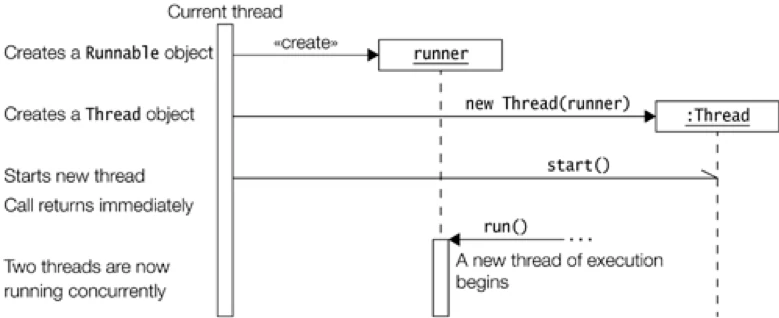

Instantiating a Thread

Remember, every thread of execution begins as an instance of class Thread. Regardless of whether your run() method is in a Thread subclass or a Runnable implementation class, you still need a Thread object to do the work.

If you extended the Thread class, it is very simple to instantiate:-

MyThread t = new MyThread();

If you are using the Runnable interface then you have to follow some simple steps:-

- You instantiate your Runnable class

MyRunnable r = new MyRunnable(); - now you get a java.lang.Thread class to execute the thread and pass your runnable class to this thread class.

Thread t = new Thread(r); // Pass your Runnable to the Thread

Now our thread class is ready to be used. You can pass a single Runnable instance to multiple Thread objects, so that the same Runnable becomes the target of multiple threads, as follows:

public class TestThreads {

public static void main (String [] args) {

MyRunnable r = new MyRunnable();

Thread foo = new Thread(r);

Thread bar = new Thread(r);

Thread bat = new Thread(r);

}

}

Giving the same Runnable to multiple threads means that several threads of execution will be running the very same job (and that the same job will be done multiple times).

Starting a Thread

Now we have our thread created (this state is of the thread is called to be in new state). And we have to start the thread, in order to start the thread we simply call the start() method of Thread class.

t.start();

When the start method is called the thread now is said to move in Runnable state, in this state the thread is waiting for its turn to come to executed by the JVM. When the run method is fired then the thread is actually running and is said to be in running state.

Putting it all together

Now let us see a simple program which uses the threads to execute. In this case we have create a FooRunnable class which implements Runnable interface.

class FooRunnable implements Runnable {

public void run() {

for(int x =1; x < 6; x++) {

System.out.println("Runnable running");

}

}

}

public class TestThreads {

public static void main (String [] args) {

FooRunnable r = new FooRunnable();

Thread t = new Thread(r);

t.start();

}

}

In this class we have overridden the run() method, in the run() method we wanted to print the string 5 times.

Then we create an instance of FooRunnable and pass this instance to the Thread instance to create a thread.

Starting and Running Multiple Threads

Enough playing around here; let’s actually get multiple threads going (more than two, that is). We already had two threads, because the main() method starts in a thread of its own, and then t.start() started a second thread. Now we’ll do more. The following code creates a single Runnable instance and three Thread instances. All three Thread instances get the same Runnable instance, and each thread is given a unique name. Finally, all three threads are started by invoking start() on the Thread instances.

class NameRunnable implements Runnable {

public void run() {

for (int x = 1; x <= 3; x++) {

System.out.println("Run by "

+ Thread.currentThread().getName()

+ ", x is " + x);

}

}

}

public class ManyNames {

public static void main(String [] args) {

// Make one Runnable

NameRunnable nr = new NameRunnable();

Thread one = new Thread(nr);

Thread two = new Thread(nr);

Thread three = new Thread(nr);

one.setName("Fred");

two.setName("Lucy");

three.setName("Ricky");

one.start();

two.start();

three.start();

}

}

Let us now understand what we are doing now in the above code, let us take the NameRunnable Class first

- NameRunnable implements java.lang.Runnable

- Override the run() method.

- In the run method we have used the Thread.currentThread() method to get the thread which is now executing in the JVM.

- We used the getName() method to get the name of the running thread.

Now let us move our focus to implementing class – ManyNames Class

- Instantiate the NameRunnable Class

- Create three different Thread object with same parameter i.e. instance of NameRunnable.

- Use the setName() method of Thread class to assign a name to the threads.

- Now start() method to start execution of the thread.

Run by Lucy, x is 1

Run by Ricky, x is 1

Run by Fred, x is 1

Run by Ricky, x is 2

Run by Lucy, x is 2

Run by Ricky, x is 3

Run by Fred, x is 2

Run by Lucy, x is 3

Run by Fred, x is 3

Note: Output will vary for each run

Thread Priorities

Threads always run with some priority, usually represented as a number between 1 and 10 (although in some cases the range is less than 10). Priorities are integer values from 1 (lowest priority given by the constant Thread. MIN_PRIORITY) to 10 (highest priority is given by the constant Thread.MAX_PRIORITY). The default priority is 5 (Thread.NORM_PRIORITY).

If a thread enters the runnable state (it means it is waiting for its turn to start executing), and it has a higher priority than any of the threads in the pool and a higher priority than the currently running thread, the lower-priority running thread usually will be bumped back to runnable and the highest-priority thread will be chosen to run. In other words, at any given time the currently running thread usually will not have a priority that is lower than any of the threads in the pool. In most cases, the running thread will be of equal or greater priority than the highest priority threads in the pool. This is as close to a guarantee about scheduling as you’ll get from the JVM specification, so you must never rely on thread priorities to guarantee the correct behavior of your program.

Setting the thread priority

A thread gets a default priority that is the priority of the thread of execution that creates it. For example, in the code the thread referenced by t will have the same priority as the main thread, since the main thread is executing the code that creates the MyThread instance.

You can also set a thread’s priority directly by calling the setPriority() method on a Thread instance as follows:

public class TestThreads {

public static void main (String [] args) {

FooRunnable r = new FooRunnable();

Thread t = new Thread(r);

t.setPriority(8);

t.start();

}

}

The sleep method ()

Suppose we want to create a stop watch which shows the digit after every one second, i.e. we want to stop the execution of the thread for some time. To do that, we will use the sleep method for the thread to stop executing.

The sleep() method is a static method of class Thread. You use it in your code to “slow a thread down” by forcing it to go into a sleep mode before coming back to runnable (where it still has to beg to be the currently running thread). When a thread sleeps, it drifts off somewhere and doesn’t return to runnable until it wakes up.

You do this by invoking the static Thread.sleep() method, giving it a time in milliseconds as follows:

try {

Thread.sleep(5*60*1000); // Sleep for 5 minutes

}

Let’s modify our Fred, Lucy, Ricky code by using sleep() to try to force the threads to alternate rather than letting one thread dominate for any period of time.

class NameRunnable implements Runnable {

public void run() {

for (int x = 1; x < 4; x++) {

System.out.println("Run by "

+ Thread.currentThread().getName()

+ ", x is " + x);

try {

Thread.sleep(1000);

} catch (InterruptedException ex) { }

}

}

}

Run by Fred, x is 1

Run by Ricky, x is 1

Run by Lucy, x is 1

Run by Fred, x is 2

Run by Lucy, x is 2

Run by Ricky, x is 2

Run by Ricky, x is 3

Run by Fred, x is 3

Run by Lucy, x is 3

The output may vary as we do not know how the threads are being scheduled during running.

Thread Synchronization - need and mechanism

Threads share the same memory space, that is, they can share resources. However, there are critical situations where it is desirable that only one thread at a time has access to a shared resource. For example, crediting and debiting a shared bank account concurrently amongst several users without proper discipline, will jeopardize the integrity of the account data. Java provides high-level concepts for synchronization in order to control access to shared resources.

To understand the problem let us take a banking example.

The Banking Example

As an application designer for a major bank, we are assigned to the development team for the automated teller machine (ATM). As our first assignment, we are given the task of designing and implementing the routine that allows a user to withdraw cash from the ATM. A first and simple attempt at an algorithm may be as follows.

- Check to make sure that the user has enough cash in the bank account to allow the withdrawal to occur. If the user does not, then go to step 4.

- Subtract the amount withdrawn from the user’s account.

- Dispense the cash from the teller machine to the user.

- Print a receipt for the user.

A simple implementation is mentioned below with some assumption. We will be focusing on mainly the design for now.

public class ATM extends Bank {

public void withdraw(float amount) {

Account a = getAccount();

if (a.deduct(amount))

dispense(amount); //Assume that this method has already been declared in Bank Class

printReceipt(); //Assume that this method has already been declared in the Bank Class

}

}

public class Account {

private float total;

public float getTotal() {

return total;

}

public void setTotal(float total) {

this.total = total;

}

public boolean deduct(float t) {

if (t <= total) {

total -= t;

return true;

}

return false;

}

}

This design works fine under normal condition, i.e. if a person wants to withdraw money and he has the required amount in his account then then money will be debited from his account.

But consider a case; it is possible for two people to have access to the same account (e.g., a joint account).

One day, a husband and wife both decide to empty the same account, and purely by chance, they empty the account at the same time. We now have a race condition: if the two users withdraw from the bank at the same time, causing the methods to be called at the same time, it is possible for the two ATMs to confirm that the account has enough cash and dispense it to both parties. In effect, the two users are causing two threads to access the account database at the same time.

- The husband thread begins to execute the deduct() method.

- The husband thread confirms that the amount to deduct is less than or equal to the total in the account.

- The wife thread begins to execute the deduct() method.

- The wife thread confirms that the amount to deduct is less than or equal to the total in the account.

- The wife thread performs the subtraction statement to deduct the amount, returns true, and the ATM dispenses her cash.

- The husband thread performs the subtraction statement to deduct the amount, returns true, and the ATM dispenses his cash.

The Java specification provides certain mechanisms that deal specifically with this problem. The Java language provides the synchronized keyword; in comparison with other threading systems, this keyword allows the programmer access to a resource in a mutually exclusive way.

public class Account {

private float total;

public synchronized boolean deduct(float t) {

if (t <= total) {

total -= t;

return true;

}

return false;

}

}

By declaring the method as synchronized, if two users decide to withdraw cash from the ATM at the same time, the first user executes the deduct() method while the second user waits until the first user completes the deduct() method. Since only one user may execute the deduct() method at a time, the race condition is eliminated.

Synchronizing a Block of Code

Let us assume we are writing a method in which we need to synchronized a couple of lines of codes, so what should we do, shall we go ahead and synronize the whole method but in that case efficiency of aur program will be reduced, since large block of code will be executed before releasing the lock.

So rather than synchronizing the whole block we will synchronize only the block of code which we want to make a thread safe.

synchronized (Account) {

if (t <= total) {

total -= t;

return true;

}

}

In this piece of code we have added synchronized key word followed by the (Account) and then our piece of code goes in the curly braces.

What we are doing here is we are trying to lock the Object Account so that no other thread can access it and then we are executing the thread safe piece of code.

Understanding Deadlocks

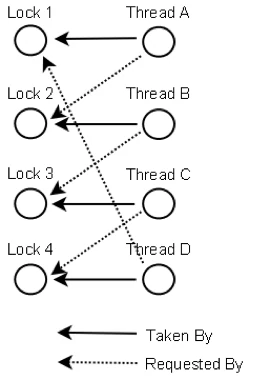

We say that a set of processes or threads is deadlocked when each thread is waiting for an event that only another process in the set can cause. Another way to illustrate a deadlock is to build a directed graph whose vertices are threads or processes and whose edges represent the “is-waiting-for” relation. If this graph contains a cycle, the system is deadlocked. Unless the system is designed to recover from deadlocks, a deadlock causes the program or system to hang.

public class Main {

public static void main(String[] args) {

final Object resource1 = "resource1";

final Object resource2 = "resource2";

// t1 tries to lock resource1 then resource2

Thread t1 = new Thread() {

public void run() {

// Lock resource 1

synchronized (resource1) {

System.out.println("Thread 1: locked resource 1");

try {

Thread.sleep(50);

} catch (InterruptedException e) {

}

synchronized (resource2) {

System.out.println("Thread 1: locked resource 2");

}

}

}

};

// t2 tries to lock resource2 then resource1

Thread t2 = new Thread() {

public void run() {

synchronized (resource2) {

System.out.println("Thread 2: locked resource 2");

try {

Thread.sleep(50);

} catch (InterruptedException e) {

}

synchronized (resource1) {

System.out.println("Thread 2: locked resource 1");

}

}

}

};

// If all goes as planned, deadlock will occur,

// and the program will never exit.

t1.start();

t2.start();

}

}

If you liked this article, you can buy me a coffee

Leave a comment